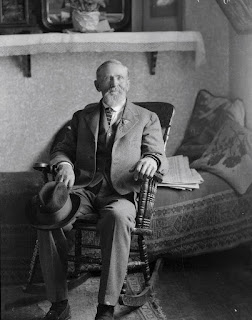

Moroni Miner: The Lesson of the Moccasin

|

| Moroni Miner |

Moroni Miner

lived to be 100 years and two months old. He was a man of great courage,

tireless industry, and sterling integrity.

The furnace

that forged Moroni’s character heated quickly in 1848. His family was trying to

cross the prairies of the Great Plains to join other members of The Church of

Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who were settling in the Rocky Mountains.

In January

1848, while in eastern Iowa, Moroni’s father, Albert Miner, died. Moroni was

not quite 13 years old. The death left his 35-year old mother, Tamma Durfee

Miner, a widow with seven children to care for. They made their way to Council

Bluffs on Iowa’s western border, where they joined

others of their family. Out of necessity, Moroni was sent out to work to help

support the family.

For the next two years, the young teenager lived temporarily

with at least three different families in Iowa and Nebraska earning money from

tending livestock, plowing fields, and cutting and hauling hay.

By June 1850, the combined family efforts finally paid off.

They had earned enough to purchase two wagons, two yokes of oxen, a few cows,

and supplies to journey to the Salt Lake Valley. They joined a wagon train and headed

west. Each of the older children was given travel assignments. Moroni’s

assignment was to drive the cows more than 900 miles. Therefore, he walked, and

he did it without shoes. When his bare feet suffered from blisters or sores,

his mother would have him soak them at night in sour milk.

After they reached Fort Bridger, Wyoming, they camped for a

few days to let the oxen rest and to prepare for the journey into the

mountains. While there, an Indian made Moroni an offer his young calloused feet

couldn’t refuse: a pair of moccasins for some flour. His mother gave Moroni a

sack of flour for the trade. The Indian took the flour, but gave Moroni only

one moccasin, saying, “More flour, other moccasin.” But Moroni’s mother

couldn’t spare any more flour, so he continued barefoot through the rugged mountains

into the Salt Lake Valley.

The lesson Moroni learned from that moccasin tempered his

character in a positive way. It was a lesson in integrity. It’s possible that

the memory of that lesson influenced him many years later when he purchased a

horse from Mr. Marchbanks. But this time the “moccasin was on the other foot”

(so to speak).

|

| Moroni and son, “Med” At Miner’s Meat Market Springville, Utah |

One day, Moroni asked his son,

Marion Francis Miner, nicknamed “Med,” to hitch up their horse and buggy for a

short three-mile drive from their farm in Springville, Utah to neighboring

Mapleton. It was Moroni’s intention to purchase a horse from Mr. Marchbanks.

After arriving at the Marchbanks’ home, Moroni looked over

the horse and began some labored negotiations and haggling with its owner.

Eventually he and Mr. Marchbanks agreed on a price and the transaction was

completed. Med rode the horse home to Springville while Moroni trailed behind

in the buggy.

About two miles into the return trip, Moroni hollered to Med that

he needed to go back to Mr. Marchbank’s, but Med should continue home. Med

brought the horse around to the buggy to ask his father why. Moroni replied, “I

have been watching that horse ahead of me all the while we have been traveling.

That horse is worth a lot more money than what I paid for it. I’m going back to

Mr. Marchbanks and pay him more money.”

Theodore Roosevelt, America’s 26th president, was a man

whose character was also forged in the furnace of tribulation. Regarding

personal integrity, he declared, “Knowing what’s right doesn’t mean much unless

you do what’s right.”

For Moroni Miner, that was the life-long lesson of the

moccasin.

-----------------------

Written and compiled by James E. Hartley, great-grandson of

Moroni Miner

-----------------------

Sources:

-----------------------