Family history can be messy. This true story is a bit on the "heavier" side containing subjects such as mental illness, prostitution, and murder, but presented in a way I think is respectful or tactful. The intent of me sharing this is to give an example where a person (who happens to be my relative albeit not very close) still gave meaningful and productive contributions to society in spite of dealing with extremely difficult personal circumstances. Another motive for me sharing this is to help us consider how we view or judge someone from the past, especially when it appears that person has done something very questionable or even immoral. Below is a story adapted and written by father, Jim Hartley, about our distant cousin William Chester Minor:

A pril 19th could be celebrated as an international holiday for all English speakers. On that day in 1928, the national British newspaper in London, The Times, announced the completion of the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. The massive dictionary was then—and still is—the world’s most comprehensive and authoritative historical dictionary of the English language. It is published and revised periodically by Oxford University Press in Oxford, England.

pril 19th could be celebrated as an international holiday for all English speakers. On that day in 1928, the national British newspaper in London, The Times, announced the completion of the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. The massive dictionary was then—and still is—the world’s most comprehensive and authoritative historical dictionary of the English language. It is published and revised periodically by Oxford University Press in Oxford, England.

The mammoth dictionary, simply known as the OED, is not your everyday dictionary. It tracks each word’s evolution: when it entered the language and how its meanings, spellings, and pronunciations changed over time.

Each definition is supported with quotations—sentences from books, newspapers and magazines—that illustrate how the word was used. The quotations are listed in chronological order showing how the meaning of a particular word has evolved.

Making the First Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary

Preparing the OED was an enormous undertaking. Work began in 1857 and was first published 70 years later in 10 volumes. That first edition in 1928 included 252,200 entries with 414,800 word-forms defined and/or illustrated with over 1.8 million quotations. The project involved more than 2,000 people.

Although the project was conceived in 1857, the dictionary didn’t begin to take shape until Sir James Murray, a remarkable Scottish scholar, became its managing editor in 1879. Dr. Murray was a linguistic genius. He knew 23 modern and ancient languages in varying degrees. He was also a true philologist—one who studies literary texts to establish their authenticity, original forms, and meanings.

Dr. Murray hired a number of editors and dozens of men and women to research and write the dictionary’s entries. In addition to his editorial staff, there were hundreds more proofreaders, consultants, and advisers. But that wasn’t enough. The dictionary’s sponsor, Oxford University, felt that the project was moving too slowly and threatened to dismiss Dr. Murray and his editors unless work was accelerated.

Responding to the University’s ultimatum, and realizing the enormity of the project, Dr. Murray published an appeal for volunteers through magazines and newspapers in the United Kingdom and in other English-speaking countries. Eventually he had enlisted more than 2,000 people in many parts of the world. They were instructed in how to supply material for the dictionary’s entries, especially quotations—examples from English texts that show how each word was actually used throughout history.

Dr. William C. Minor, American Surgeon and Major Contributor

One individual in particular became Dr. Murray’s most prolific contributor, Dr. William C. Minor, a medical surgeon from America, who resided at Broadmoor, Crowthorne, Berkshire in England.

One individual in particular became Dr. Murray’s most prolific contributor, Dr. William C. Minor, a medical surgeon from America, who resided at Broadmoor, Crowthorne, Berkshire in England.

At Broadmoor, Minor maintained a large, private library of modern and ancient books, some published during the 1600s and 1700s. To make his work on the dictionary easier, Minor meticulously indexed the words in his books and used those indexes to identify quotations for the dictionary.

Oxford’s first request to Minor was for the word, “art.” The editors had discovered 16 meanings but were convinced more existed. When Dr. Minor searched his indexes, he found 27. The Oxford staff was overjoyed. Soon, Dr. Minor became the team’s go-to resource for troublesome words.

Every week for the next 20 years, Dr. Minor faithfully provided notes and research to the editors in Oxford. By the time he returned to the United States in 1910, he had submitted tens of thousands of individual entries for the OED. Because of his extensive work on the dictionary, he was acknowledged by Dr. Murray as one of history’s great contributors to the English language. In fact, in the OED’s first volume—then called A New English Dictionary, published in 1888—Sir James Murray added a line of thanks to “Dr. W. C. Minor, Crowthorne.”

In the preface of the fifth volume of the OED, Dr. Murray again published a note of acknowledgment: “Second only to the contributions of Dr. Fitzedward Hall [one of the OED’s earliest major contributors], in enhancing our illustration of the literary history of individual words, phrases, and constructions, have been those of Dr. W. C. Minor, received week by week….”

Years later, Dr. Murray wrote: “So enormous have been Dr. Minor’s contributions during the past 17 or 18 years, that we could easily illustrate the last four centuries [of each word] from his quotations alone.”

On a visit to England, the librarian of Harvard College thanked Dr. Murray for being so kind to ''our poor Dr. Minor.'' ''Poor Dr. Minor?'' Dr. Murray was puzzled. ''What can you possibly mean?''

Dr. Murray knew that all of Dr. Minor’s notes were sent from the Broadmoor, the Criminal Lunatic Asylum in Crowthorne. But he assumed that Minor was a medical doctor on staff at the asylum. He was dumbfounded to learn that “poor Dr. Minor” was actually an inmate at the asylum—patient number 742—who had suffered for decades with delusions, hallucinations, and paranoia, and was a convicted murderer.

William C. Minor’s Tortured History

In 1833, Eastman Strong Miner and his wife, Lucy Bailey Miner, left New England to serve as Congregationalist Church missionaries on the island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), a British colony off the southeastern tip of India. While there, William Chester Minor was born on June 22, 1834, and two years later, his sister, Lucy, was born.

But little William’s life was permanently shaken at age three when his mother died. Two years later, his father remarried. William’s stepmother, Judith Manchester Taylor, was also an American Congregationalist missionary. During the next nine years, six of William’s eight half-brothers and sisters were also born in Ceylon.

When William was 14 years old, his father and stepmother thought it was best to send him 8,600 miles away to live with relatives in New Haven, Connecticut. He could receive a better education there and he would be near extended family. But, to young William, it was like being exiled to an alien foreign country to live with complete strangers. He had only known life in Ceylon with his immediate family.

Shortly after his arrival in New Haven in 1848, William was enrolled in a local school called the New Haven Collegiate and Commercial Institute (commonly known as the Russell Military Academy). It was a three-year school to prepare older boys for college. Its curriculum included Latin, Greek, natural science, mathematics, history, English, and other modern languages. In addition to their studies, students also participated in a daily military drill wearing cadet uniforms. The school had approximately 130 students and 12 instructors.

William appeared to adapt reasonably well to New Haven and its academy. During that time, he also developed interests in reading, painting with watercolors, and playing the flute.

Sometime after graduation from the academy, he enrolled at Yale University and in 1861 entered its medical school. He supported himself during his college years with part-time employment as an instructor at the Russell Military Academy and as an assistant helping to compile the 1864 revision of Webster’s Dictionary, then in preparation at Yale in New Haven … an experience that prepared him for his involvement years later in the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary.

In 1863, at age 29, Minor graduated from Yale University with a medical degree. In that year, the U.S. Civil War was in full rage, engulfing the entire nation. Minor joined the Union Army as a lieutenant and as a surgeon. For a short time, Lieutenant Minor did research at the Knight Hospital in New Haven, where he prepared detailed autopsy reports of soldiers who died from various lung ailments.

Attending to the Wounded

In May 1864, Lieutenant Minor was transferred to Alexandria, Virginia, to help care for the staggering number of Union soldiers from the Army of the Potomac’s Second Division, who were wounded during the Battle of the Wilderness. That battle was a gruesome engagement between the forces of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant’s Union army and General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate troops.

The Battle of the Wilderness was, in fact, the fourth bloodiest battle of the Civil War. Union casualties were estimated at well over 17,000, including more than 10,200 wounded. Total Confederate casualties were numbered at 11,400 with 8,000 wounded.

The Battle of the Wilderness was Lieutenant Minor’s first exposure to patients torn, mangled, and burned from combat and diseased from exposure, poor hygiene, and malnutrition.

In addition to the extreme casualties of the battle, desertion was a serious problem. During the Civil War, the punishment for desertion was death. But during the Battle of the Wilderness, there were unconfirmed accounts that some may have instead been punished by branding the letter “D” for “deserter” into the soldier’s cheek. Moreover, there is an unverified story that Lieutenant Minor had been ordered to brand a young Union Irish soldier, and that traumatic incident later played a role in Minor's delusions; he believed the Irish soldier would somehow seek revenge.

For two years, Lieutenant Minor continued helping patients. He was promoted to assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army and received the rank of captain.

Paranoia at Governor’s Island  After the war, Captain Minor was transferred to the Army hospital on Governor’s Island, New York, where he treated cholera patients. While there, a group of thugs mugged and murdered one of his fellow officers in Manhattan. The murder of his friend triggered an intense paranoia within him and it most likely opened the floodgates of repressed emotions of abandonment as a child and extreme trauma from the horrors of the Civil War.

After the war, Captain Minor was transferred to the Army hospital on Governor’s Island, New York, where he treated cholera patients. While there, a group of thugs mugged and murdered one of his fellow officers in Manhattan. The murder of his friend triggered an intense paranoia within him and it most likely opened the floodgates of repressed emotions of abandonment as a child and extreme trauma from the horrors of the Civil War.

Minor snapped. He began carrying a Colt .38 to protect himself from would-be assailants, who he was certain were all around him. He sought refuge with prostitutes—an activity that evolved from an urge, to a compulsion, and to a nightly addiction; an activity that compounded his misery with venereal disease.

His mental and physical illnesses hampered his medical performance on Governor’s Island. Consequently, the Army assigned him to Fort Barrancas, a remote outpost located in the extreme western panhandle of Florida, near Pensacola, on the Gulf of Mexico.

In Florida, Captain Minor’s mental condition continued to deteriorate. His grasp of reality became increasingly foggy. In 1868, he was diagnosed as delusional and was considered a suicide and homicide risk.

He was willingly admitted to the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C. (known as St. Elizabeths Hospital), and officially retired from the U.S. Army with an honorable medical discharge and full pension.

He was willingly admitted to the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C. (known as St. Elizabeths Hospital), and officially retired from the U.S. Army with an honorable medical discharge and full pension.

After nearly three years at St. Elizabeths, Minor was released. Believing that a change of scenery would help him, he took his military pension and sailed to England.

He eventually settled in the south London borough of Lambeth, at the time, a slum area where his addiction for prostitutes quickly reclaimed him.

Haunted by Delusions and Hallucinations

Along with enslavement by his physical passions, he was haunted by nighttime delusions and hallucinations that became more and more frequent. He was certain that young boys were watching him and he could hear their footsteps as they prepared to smother his face with chloroform. He laid helplessly in bed as imaginary men barged into his room, shoved funnels into his mouth, and poured chemicals down his throat. He was petrified when invisible invaders entered with knives and instruments of torture to operate on his heart. Other apparitions forced him into sordid acts of depravity. One time, fictious harassers kidnapped him and transported him during the night to Constantinople (now Istanbul), Turkey, and forced him to perform unspeakable acts.

He was certain that most of his attackers were members of an Irish nationalist group called the Fenian Brotherhood that was not only determined to overthrow British rule, but was equally committed to exacting revenge on Minor for branding the young Union Irish soldier. He envisioned Irish rebels huddled together in the darkness under gas streetlights, whispering plans of his torture and poisoning.

All of his imagined attackers were very real to him. On multiple occasions, he reported the invasions to the local police. In a sworn court statement, Frederick Williamson, superintendent of Detective Police, reported, “I first knew [William C. Minor] on the 27th of December last, when he came to me at Scotland Yard, and told me … he had just come from America. He said he left [America] to avoid persecution by the Irish and he appeared to me to be under a delusion. Between that and the 31st of January last, he called on me several times. One of his statements was that when he awoke in the morning, he had burning sensations in the stomach, which he believed was caused by some person who was invisible to him coming into his room in the night time and putting some kind of poison in his mouth…. We had never considered him to be dangerous, but we thought he was subject to delirium.”

Each time Minor tried to report the invasions, the detectives would politely nod and scribble something down. But when nothing changed, he decided to handle the problem himself: He tucked a loaded pistol, a Colt .38, under his pillow. He barricaded his locked door with chairs and desks. He fashioned traps, tying a string to the doorknob and connecting it to a piece furniture so that when somebody opened the door, the furniture would screech across the floor like a burglar alarm. But none of this helped his condition.

Murder at the Lion Brewery On February 17, 1872, Minor was suddenly awakened just before 2:00 am by a man standing in his bedroom. This time, Minor did not lay still. He reached for his gun. As the intruder bolted for the door, Minor threw off his blankets and sprinted outside with his weapon. He looked down the cold, wet road and spotted a man walking briskly away. William chased him. Four shots rang out; the first two missed their mark, but the final two delivered fatal wounds to the man’s neck.

On February 17, 1872, Minor was suddenly awakened just before 2:00 am by a man standing in his bedroom. This time, Minor did not lay still. He reached for his gun. As the intruder bolted for the door, Minor threw off his blankets and sprinted outside with his weapon. He looked down the cold, wet road and spotted a man walking briskly away. William chased him. Four shots rang out; the first two missed their mark, but the final two delivered fatal wounds to the man’s neck.

The man, of course, was real and not an imagined intruder. His name was George Merrett, a 34-year-old husband and father of seven children. His wife, Eliza, was pregnant with their eighth. George had walked to work that early morning as he had every workday morning for the previous three weeks; he stoked coal at the Lion Brewery. He was gunned down by Minor only a few feet from where had been employed for eight years.

At his trial, the jury found Minor guilty of willful murder. But, about seven weeks later, after investigating and observing his mental condition, the court changed its decision to “not guilty on the grounds of insanity.” Minor was then committed to the Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane, where he remained for 38 years.

The Asylum

While in Broadmoor, Minor’s nighttime torturous hallucinations continued. But during the daytime, to all outward appearances, he remained a dignified, solitary figure. Dr. Minor’s status as a surgeon was respected. The asylum gave him two adjacent rooms, one for sleeping and one for his activities, such as painting in watercolors, playing his flute, and reading. By day, he enjoyed freedom to stroll around the grounds and generally do whatever he wanted to. Thanks to his U.S. Army pension, he lived in relative luxury; he was allowed to buy steak, wine, brandy, newspapers, and books—lots of books—for his ever-expanding, private library. He even hired other inmates to perform chores for him.

About seven years into his confinement, he became genuinely remorseful for killing George Merrett, and formally apologized to his widow, Eliza. Minor began sending money on a regular basis to her and her children. At Minor’s request, Eliza eventually visited him at Broadmoor. She said that she forgave him, and she even made periodic deliveries of books he had arranged to purchase.

About the same time that Minor began communicating with Eliza Merrett, he responded to Sir James Murray’s plea for volunteers to assist with the Oxford English Dictionary. Dr. Murray was soon amazed by the quantity and quality of Minor’s submissions. Even after Dr. Murray realized “poor Dr. Minor's” true condition, he still regarded him as his most reliable source, a madman whose words were very much to be trusted.

It was 12 years before the two personally met at Broadmoor. In 1891, Dr. Murray visited Minor and they spent several hours that day conversing in Minor’s cell. Their meeting proved to be the beginning of an enduring friendship.

Dr. Murray visited Minor at Broadmoor on many occasions over the next 19 years until Minor, at age 76, was granted permission to return to the United States to live out his last days. Minor’s half-brother, Alfred, traveled to England to escort him on his homeward journey.

After Minor left England, the Broadmoor Asylum cleared out the stacks of precious books that he had so meticulously indexed and consulted when working on the Oxford English Dictionary. Eventually, they were donated to Oxford University and today they are archived in the university’s expansive Bodleian Library. The collection also includes at least 42 of Minor’s famed word indexes.

William Minor returned to the Government Hospital for the insane in Washington, D.C. (St. Elizabeths Hospital). During the nine years he lived there, he was diagnosed as suffering from a newly-defined psychosis called schizophrenia.

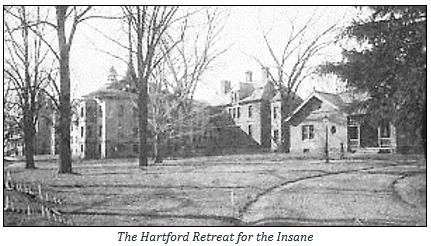

In 1919, Minor’s nephew successfully petitioned to have his uncle moved to a hospital in Hartford, Connecticut closer to his family. The hospital was called The Hartford Retreat for the Insane and was an upper-class, resort-like facility.

Less than a year later, on March 26, 1920, Minor died of pneumonia in his sleep at age 85. His remains were interred at Evergreen Cemetery, New Haven, Connecticut, the city where teenaged William Minor began his American experience. William never married and, as far as anyone knows, never had any offspring.

For many people, being institutionalized at an asylum marked the end of their useful lives. But not William Minor. From the solitude of his cell in Broadmoor’s Cell Block Two, he had become the most productive and successful outside-contributor to the most comprehensive reference book in the English language: The Oxford English Dictionary. Despite his extreme mental instability and criminal act, Dr. William C. Minor should be remembered as a brilliant scholar, who achieved amazing intellectual feats that continue to bless the entire English-speaking world.

-----------------------------------------

Written and compiled by James E. Hartley, sixth cousin, three times removed from William Chester Minor. The writer is related through his mother, Norma Miner Hartley.

IT SHOULD BE NOTED that the spelling of William’s surname, “Minor,” ends in “or.” Genealogical records show that the alternate spelling of “Miner,” ending in “er,” was used by his father, uncle, and most of his aunts. These two spellings are found throughout the family pedigree.

-----------------------------------------

Sources

· https://public.oed.com/blog/1928-year-of-the-dictionary/

· https://public.oed.com/history/oed-editions/

· https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Murray_(lexicographer)

· https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Chester_Minor

· https://www.nytimes.com/1998/09/07/books/the-strange-case-of-the-madman-with-a-quotation-for-every-word.html

· http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/myths_legends/england/berkshire/article_1.shtml

· https://forgottennewsmakers.com/2010/11/08/dr-william-minor-1834-1920-insane-doctor-who-contributed-to-the-oxford-english-dictionary/

· https://stonesentinels.com/the-wilderness/battle-wilderness-facts/

· https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/09/18/sad-life-william-chester-minor-one-largest-contributors-oxford-english-dictionary-held-lunatic-asylum-murder-time/

· https://murderpedia.org/male.M/m/minor-william-chester.htm

· https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/504609/murderer-who-helped-make-oxford-english-dictionary

· https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadmoor_Hospital

· https://allthatsinteresting.com/oxford-english-dictionary-history/2

· https://connecticuthistory.org/hartford-retreat-for-the-insane-advanced-improved-standards-of-care/

· https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/2N6Z-P92 (Dr. William Chester Minor)

· https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/2N6Z-PMH (Eastman Strong Miner)